This Book Explains Why Yobs & Criminals Should Rule the World

This Book Explains Why Yobs & Criminals Should Rule the World

The WSJ has an article on Eric Hobsbawm, who is now silly at age 94---just as he has been all his life. I happen to be reading Tony Judt's Reappraisals which has a chapter on EH called "Eric Hobsbawm and the Romance of Communism." Here's Judt on EH:

"There are certain clubs," he has said, "of which I would not wish to be a member." By this he means ex-Communists. But ex-Communists---Jorge Semprun, Wolfgang Leonhard, Margarete Buber-Neumann, Cklaude Roy, Albert Camus, Ignazio Silone, Manes Sperber and Arthur Koestler---have written some of the best accounts of our trerrible times. Like Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov, and Havel (whom Hobsbawm never mentions), they are the twentieth century's Republic of Letters. By excluding himself, Eric Hobsbawm has provincialized himself. [I would have included Whittaker Chambers' impassioned Witness among those representatives of the Republic of letters. Eds note!] [p. 123, Reappraisals

Tony Judt then does an entomolygists' excellent job of dissecting and then pinning this insect to the glass-enclosed mortuary where EH & his fellow fools belong. The WSJ does a good job at embalming this living fossil:

To his critics, his ideological dogmatism has made him an untrustworthy chronicler of the 20th century. The British historian David Pryce-Jones argues that Mr. Hobsbawm has "corrupted knowledge into propaganda" and is a professional historian who is "neither a historian nor professional." Reading his extravagantly received 1994 book, "The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914-1991," the celebrated Kremlinologist Robert Conquest concluded that Mr. Hobsbawm suffers from a "massive reality denial" regarding the Soviet Union.

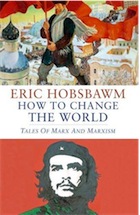

In "How to Change the World: Reflections on Marx and Marxism," Mr. Hobsbawm's latest attempt to grapple with Karl Marx's legacy of ashes, the author remains an accomplished denier of reality. Drawn from essays and speeches spanning the past 50 years, Mr. Hobsbawm's book ruminates on pre-Marxian socialism, the works of the Italian communist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, and a slew of internecine ideological battles that will be of interest mainly to academics and unreconstructed militants.

The more recent material in "How to Change the World," written after the fall of the Soviet Union, claims that regimes self-identified as Marxist shouldn't be allowed to sully the reputation of Marxism—despite all the statues of Marx that once dotted the communist world, the constant invocations of "Das Kapital" and "The Communist Manifesto," and the savage collectivization schemes.

The Wall Street Journal goes on to do a less subtle job of unmasking this impostor than Tony Judt did, but with an apologist for the mass murders committed by Stalin, Chairman Mao, Pol Pot and the currently starving subjects of Kim Jung-Il, subtlety isn't an appropriate tool. A good old-fashioned shillelagh or baseball bat such as those employed by his followers in the UK plundering and looting last night is a good weapon to employ on this intellectual criminal.

For anyone who has visited an American college campus in the past half-century, Mr. Hobsbawm's core argument will be familiar: The Marxism practiced by Lenin, Stalin and Mao was a clumsy misinterpretation of Marx's theories and, as such, doesn't invalidate the communist project. True, the East Bloc societies practicing what was called "actually existing socialism" (which Mr. Hobsbawm determines, ex post facto, didn't actually exist) ended in economic disaster, but experiments in "market fundamentalism also failed," he says. It is unclear to which "fundamentalist" governments he is referring, but it's important for Mr. Hobsbawm to establish a loose moral equivalence between Thatcherism and the ossified economies controlled or guided by Moscow.

One wouldn't know it from "How to Change the World," but Mr. Hobsbawm wasn't always convinced that the Soviet Union, along with its puppets and imitators, was misunderstanding the essence of Marxism. He never relinquished his membership in the Communist Party, even after Moscow's invasions of Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Indeed, he began his writing career with a co-authored pamphlet defending the indefensible Soviet invasion of Finland in 1939. "To this day," he writes in his memoirs, "I notice myself treating the memory and tradition of the USSR with an indulgence and tenderness." There was some ugliness in the socialist states occupied by Moscow, he admitted in 2002, but "leaving aside the victims of the Berlin Wall," East Germany was a pleasant place to live. Other than that, how was the play, Mrs. Lincoln?

In a now infamous 1994 interview with journalist Michael Ignatieff, the historian was asked if the murder of "15, 20 million people might have been justified" in establishing a Marxist paradise. "Yes," Mr. Hobsbawm replied. Asked the same question the following year, he reiterated his support for the "sacrifice of millions of lives" in pursuit of a vague egalitarianism. That such comments caused surprise is itself surprising; Mr. Hobsbawm's lifelong commitment to the Party testified to his approval of the Soviet experience, whatever its crimes. It's not that he didn't know what was going on in the dank basements of the Lubyanka and on the frozen steppes of Siberia. It's that he didn't much care.

So why is this apologist for Hitlerian genocide and "ethnic cleansing" getting knighted by a Queen obviously as obtuse as this criminal is guilty of "thought crimes" to use an Orwellian phrase? I guess it's EH's constant use of the phrase "need not detain us here or some such silly variation of his moronic thinking worthy of a Nancy Pelosi's "We have to pass the bill in order to see what's in it."

Readers of "How to Change the World" will be treated to explications of synarchism, a dozen mentions of the Russian Narodniks, and countless digressions on justly forgotten Marxist thinkers and politicians. But there is remarkably little discussion of the way communist regimes actually governed. There is virtually nothing on the vast Soviet concentration-camp system, unless one counts a complaint that "Marx was typecast as the inspirer of terror and gulag, and communists as essentially defenders of, if not participators in, terror and the KGB." Also missing is any mention of the more than 40 million Chinese murdered in Mao's Great Leap Forward or the almost two million Cambodians murdered by Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge.

When the bloody history of 20th-century communism intrudes upon Mr. Hobsbawm's disquisitions, it's quickly dismissed. Of the countries occupied by the Soviet Union after World War II—"the Second World War," he says with characteristic slipperiness, "led communist parties to power" in Eastern and Central Europe—he explains that a "possible critique of the new [postwar] socialist regimes does not concern us here." Why did communist regimes share the characteristics of state terror, oppression and murder? "To answer this question is not part of the present chapter."

Regarding the execrable pact between Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia, which shocked many former communist sympathizers into lives of anticommunism, Mr. Hobsbawm dismisses the "zig-zags and turns of Comintern and Soviet policy," specifically the "about-turn of 1939-41," which "need not detain us here."

The WSJ writer wisely turns us to another writer who merits an entire chapter, this one totally approving, in Judts's Reappraisals: Judt's Chapter following Hobsbawm's tomfoolery is entitled: "Goodbye to All That: Leszek Kolakowski and the Marxist Legacy [pp.129-146]

In one sense, Mr. Hobsbawm's admirers are right about his erudition: He possesses an encyclopedic knowledge of Marxist thought, specifically Italian communism and pre-Soviet socialist movements. But that knowledge is wasted when used to write untrustworthy history. Readers interested in a kaleidoscopic history of Marxist thought, its global influence and the reasons why regimes flying the red banner inevitably resorted to slavery and violence would be better served by Leszek Kołakowski's "Main Currents in Marxism." The three-volume classic (published in English in 1978 and in 2005 as a single volume) ably demonstrates that Stalinism is a feature of Marxism, not an aberration.

Mr. Hobsbawm closes "How to Change the World" by making a predictable admonition: With the world economy in turmoil, "once again the time has come to take Marx seriously." How the application of Marxist economics to the deeply indebted U.S. (or Greek) economy would reverse the current crisis is left unsaid. In Europe, where socialist parties and left-wing coalitions win elections, the electoral tide has turned dramatically in the other direction now that social-democratic policy has swamped the Continent in debt, with parties of the right controlling all of the major (and many minor) economies.

"How to Change the World" shows us little more than how an intellectual has committed his life not to exploring and stress-testing an ideology but to stubbornly defending it. The brand of Marxism that Eric Hobsbawm champions is indeed a way to "change the world." It already did. And it was a catastrophe.

Whenever a living fossil like Hobsbawm comes out of his kennel to bark at his mental masters, I recall the comment renowned Commie Berthold Brecht was heard muttering under his breath when the GDR's version of the Politburo followed the Berlin 1953 Labor Riots by workers unhappy living in their paradise with the admonition that "Perhaps the German People are not yet deserving of a Marxist/Leninist workers' paradise: Brecht muttered back a response "Well, then. Perhaps the GDR politburo should find itself a new population of compliant citizens..."

No comments :

Post a Comment